Description:

Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) inherited his love for art and romantic literature, especially the poetry of Juliusz Słowacki, from his family home. He came from an aristocratic, albeit impoverished, family. His father Julian supported him on the path of a painting career. The events of 1863, the January Uprising and subsequent repression, left a deep mark on the young artist. His first teacher was Adolf Dygasiński. He spent his youth from 1867 to 1871 at the Karczewski mansion in Wielgiem. In 1873 he began his studies at the School of Fine Arts in Krakow under the tutelage of Jan Matejko. He was a student of Władysław Łuszczkiewicz. He also studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He traveled to Italy, Vienna, Munich, Greece, and Minor Asia. From 1896 to 1900 and 1910 to 1914 he was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. From 1912 to 1914, he was its rector. He began with idealizing realism, then naturalism, with the main theme of his works in this period being the fate of exiles in Siberia and the inspiration of Juliusz Słowacki’s “Anhellim”. At the same time, fantastic and allegorical approaches began to appear in Malczewski’s work. After his father’s death in 1884, the recurring motif in Malczewski’s work was Thanatos – the god of death. After 1890, his art became thoroughly symbolic. Works manifesting the shift towards the style of symbolism are: “Introduction” 1890, “Melancholy” 1890-1894, “Vicious Circle” 1895-1897. The artist addressed existential, historical, and artistic issues, intertwining ancient and biblical motifs with native folklore and the so important Polish landscape in his works. Form, color, monumentality of representations and their expressiveness became his hallmark.

Description of the painting:

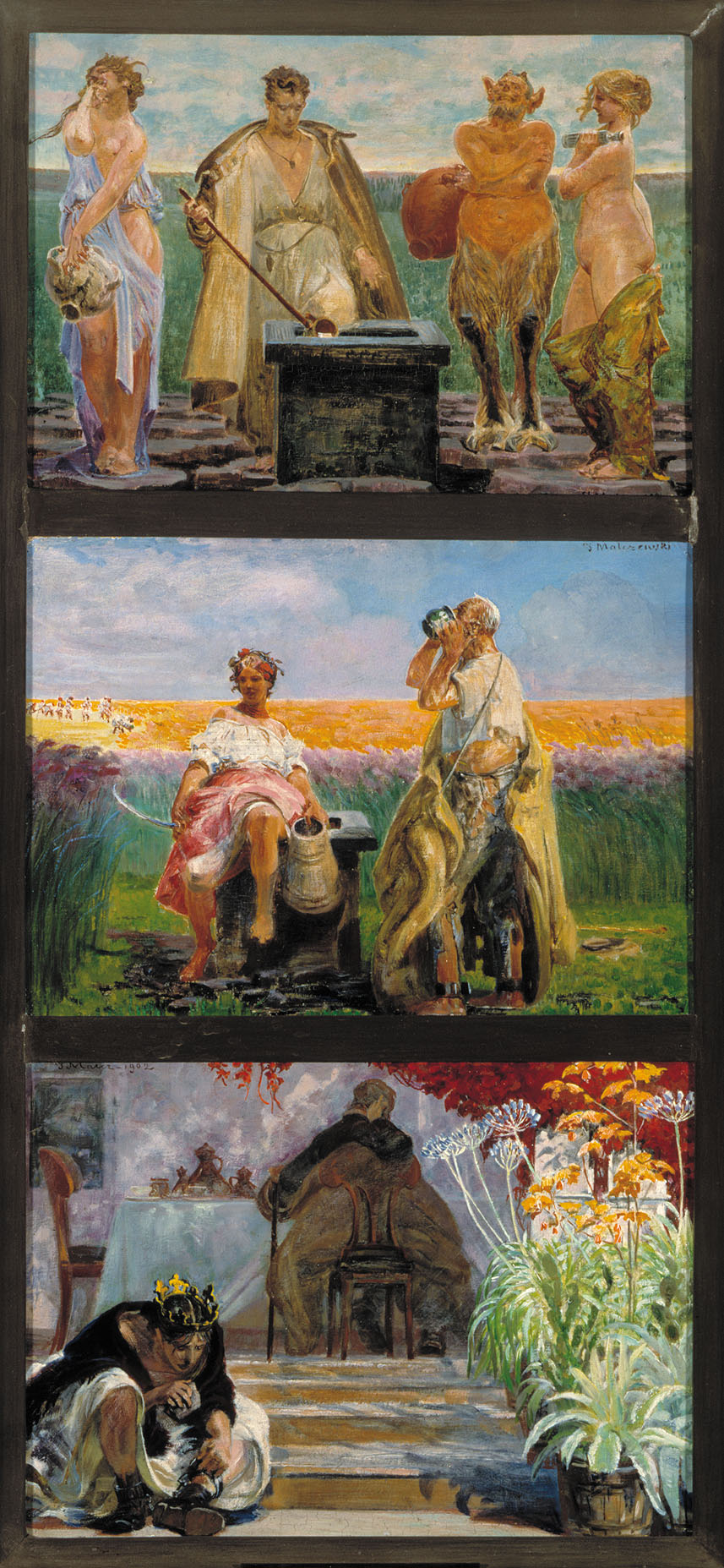

In the triptych “Fairy Tales II” three unrelated narrative events have been presented. The subject around which the action revolves is the symbolic well located among the fields. It is to it that the visitors are heading, including a man in a Siberian coat. In this context, the well becomes a magical place where figures of fantasy and mythology meet with the man-artist. Everyone wants to quench their thirst. The work has significant patriotic references. The woman sitting on the last presentation in a crown, freeing herself from shackles, is the personification of Polonia. In the triptych, therefore, threads concerning the status and duties of the artist, the purpose of his actions and the fate of the enslaved Homeland are intertwined. You can read more about the symbols appearing in the triptych in the text below.

The top panel of the triptych: Among the fields in the distance, a well stands. Four figures have gathered around it. A young man with a scapular on his chest and a Siberian cloak thrown over his shoulders is drawing water. The well in the center of the scene is flanked by two women. The woman standing to the left averts her gaze and looks carefree into the sky. The girl on the right hand side holds up her fabric, revealing her body completely. Next to the man, a faun is painted. He looks at the viewer with a smile. He holds his arms crossed over his chest and waits.

The symbolism of the well is very elaborate. It often becomes a mysterious passage between two worlds connected by it. The underworld from which it draws and the earthly one, above its surface, which uses its resources. Due to its dual nature, we can interpret its presence extremely differently. On the one hand, as something positive, when it becomes a source of living water. Water from the well can restore health and life. However, it should be remembered that it is also a place of death, fear of its depths, or a cluster of demonic forces. For both these reasons, it was necessary to have guardians* guarding access to it.

Pay attention to the vessels held in the hands of the thirsty newcomers. The young man in a Siberian cloak used a jug, through whose ear he passed the curved part of a wooden ladle which is familiar to us from other representations. Thanks to that he reached the mirror of water. The satyr holds a large earthenware jug, which certainly won’t fit into the well. The woman-muse in a blue peplos, a characteristic Greek garment, holds a vase with four handles in her hand. The woman-chimera, covering only her legs, holds a small incised bottle. There is no bucket or guardian at the well to help draw water from it. The man, as the only one, thanks to the use of the wooden ladle, quenches his thirst. And only he can help the others waiting to obtain the life-giving liquid.

The middle panel of the triptych:

The scene has been shifted back, closer to the fields. In the background one can see the ongoing harvest. It is the fullness of summer. An old man has stopped by the well. His clothes are tattered. On the string tied around his chest he has hung a fur coat. He wears shackles on his feet, but the chain connecting them has already been broken. On the ground, next to him, lies a soldier’s cap and a wooden staff. The man quenches his thirst with water from a small jug. The guardian of the well has sat down next to him. The young woman reveals her thighs. Her blouse has been slid off, exposing her bare shoulders. Her feet are bare. She has poppies and cornflowers braided into her hair. In her right hand, the girl holds a scythe. In her left hand, she holds a wooden pail. The woman is not looking at the man; her gaze seems to encompass the fields around them.

The guardian tempts with the sensuality of her body and its life-giving energy. The poppies adorning her head are symbols of fertility, but also of sleep and death. The latter takes on significance in connection with the scythe she holds and the ongoing harvests. For balance, next to the poppies appear the cornflowers, fulfilling protective and healing functions, like the water with which the old man quenches his thirst. Youth, vitality, sensuality are opposed to the mature age, the weariness of the man. The wanderer has reached his destination. He has discarded his wooden staff. He no longer needs it. The journey has come to an end. He lacks strength, but soon he will find respite.

The bottom panel of the triptych:

Autumn has come. A man is sitting on the porch of a typical Polish manor. His torso is dressed in a brown Siberian cloak. His left hand is resting on a wooden cane. On the table next to him stand pitchers and cups. The man is waiting for someone. He places his right hand to his ear and listens. In the foreground we see a woman. She has sat for a moment on the steps of the manor. On her head she wears a crown. She is dressed in white and red robes. This is the personification of Polonia. Enslaved, she has decided to free herself from the shackles, striking the chain with a stone in her hand. The clang of the targeted chain caught the man’s attention. But he does not get up from the table. He remains turned away from the viewers.

A similar manor can be seen in the triptych “Bajki I”. On his porch, a young faun was cleaning his shoes. The building, which often appears in the painter’s works, is identified as the family home of the Karczewscy in Wielgie, the Malczewski’s uncle, where he spent part of his youth. A familiar and safe place. It is often referred to as the painter’s “mythical land” in which his artistic sensitivity was formed**. And it is at the entrance of this house that Polonia appears. The clanging of the chain has caught the man’s attention, will he make his way towards her? At this moment, the stories told in “Bajki” come to an end.

The triptych “Fairy Tales II” – interpretation of the whole:

The work presents a sequence of three events unrelated to each other narratively. The object around which the action is again focused is a well located among the fields. It is to this well that the visitors come, including a man in a Siberian coat. Presented in the first part as a young man, in the second he has the features of an old man, heading towards the end of his journey. In this context, the well becomes a magical place, where fantastic and mythological characters meet with a person. A muse, the source of artistic inspiration, a chimera – tempting, tempting with its sensuality and exploiting human weaknesses, a naturally naughty satyr and a guardian-death. Everyone wants to quench their thirst.

In the three paintings of the triptych, the wooden stick appears again. On the one hand, it serves as an aid in action, such as when fetching water from the well, on the other – it becomes a sign of the restrictions and physical disabilities associated with the passage of time and the journey travelled. It is on this stick that the inhabitant of the manor rising from his chair will be supported. Similarly with the Siberian coat. Regardless of whether it is a reference to patriotic and historical allusions or a symbol of external and internal limitations of the painter, it has been captured in all of the paintings of Malczewski’s “Fairy Tales” series.

A coat and a wooden cane become thus attributes of Malczewski-the artist, who hears the cry of longing for the liberation of Poland. “Believe me, if I were not a Pole, I would not be an artist. On the other hand, I have never narrowed the Polishness of my art to certain narrow, pre-defined frames. Wyspianski, for example, limited the concept of Polishness to one place. He often took me to Wawel and said: ‘This is the Polishness’. Meanwhile, I always told him that Poland is these fields, hedges, roadside willows, the mood of this village at sunset, such a moment as now – all of this is more Polish than Wawel, this is what an artist-Pole should strive to express first and foremost.”***.

According to Zygmunt Batowski, Jacek Malczewski’s “Fairy Tales I” and “Fairy Tales II” were displayed together with “Self-Portrait with Hyacinth” as a middle presentation, creating a triptych arrangement. Paintings from the “Fairy Tales I” and “Self-Portrait with Hyacinth” series are displayed in the National Museum in