Description:

Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) inherited his love for art and Romantic literature, particularly the poetry of Juliusz Słowacki, from his family home. He came from an aristocratic, but not wealthy, family. His father Julian supported him in his career as a painter. The events of 1863, the January Uprising and subsequent repression, left a strong impression on the young artist. His first teacher was Adolf Dygasiński. Between 1867 and 1871 he spent time in the family estate of the Karczewskis in Wielgim. In 1873 he began studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow under the tutelage of Jan Matejko. He was a student of Władysław Łuszczkiewicz and also studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He traveled to Italy, Vienna, Munich, Greece, and the Minor Asia. Between 1896 and 1900, and 1910 and 1914, he was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. From 1912 to 1914 he was its rector. His early works were characterized by idealized realism, followed by naturalism. During this period, his works were often inspired by Juliusz Słowacki’s poem, “Anhellim”, and the fate of the exiles to Siberia. At the same time, his works began to take on a more fantastical and allegorical tone. After his father’s death in 1884, the motif of Thanatos – the god of death – began to appear in Malczewski’s works. After 1890, his art became increasingly symbolic. Works such as “Introduction” (1890), “Melancholy” (1890-1894) and “Vicious Circle” (1895-1897) marked the transition to a more symbolic style. The artist explored existential, historical and artistic themes, often interweaving classical and biblical motifs with Polish folklore and landscapes. His works were distinguished by their form, colour, monumental scale, and expressive power.

Description of the painting:

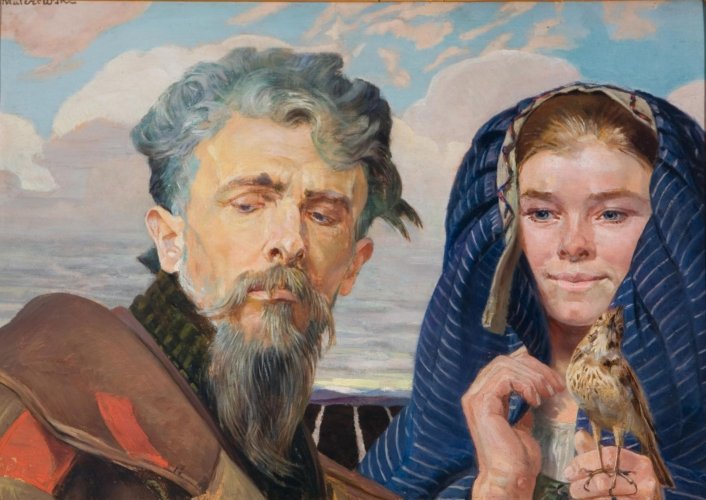

After 1900, the landscape in Malczewski’s works became an “accompaniment to the expression of the human. It is a supplement to the painting, telling about the man, about his life and his soul. That is why Malczewski treats the landscape somewhat superficially. He finishes it as much as necessary to communicate with the viewer. He paints the landscape almost always from memory. Hence, there is almost a stenographic shortcut of the landscape, as if it were a summary. Landscape motifs are rather signs […] [The artist throughout his creative period – A.W. note] did not get rid of the humility towards nature – which he proclaimed. “* On the painting, Malczewski captured two figures – a woman and a man. The girl looks to the left. It seems to see more than what is given to the viewer. The woman has a navy bow decorated with thin white stripes on her neatly tied hair. On her left hand, a sparrow has settled. She holds the hem of the fabric covering her head with her right hand. To the right of the woman, the artist painted her companion. An older man with gray hair and beard was dressed in a Siberian coat. He is identified as Wójcicki from Zwierzyniec, Jack Malczewski’s favorite model. Like the girl, he looks down, intrigued by the scene playing outside the frame of the painting. Both figures were depicted against a blue sky decorated with tufted clouds and stretches of land waking up slowly from the winter lethargy of the fields.

Significant in the work is the dualism multiplied by the painter. The opposition of two sexes – woman and man, two periods of life – young, full of vital forces, just awakening to life, and mature, experienced, burdened with the past, which hangs on the shoulders like a brown scapular imposed on them. We find a similar, antagonistic approach in the accompanying landscape. The clearly outlined line of the horizon separates the sky and the earth, symbolically representing the spiritual and physical sphere. This division is enhanced by the expression of the eyes painted on the figures, which lower their gaze, directing it towards the earth from which they live, which they have managed to tame with their work, but to which they remain completely subordinate. Two opposing worlds seem to be connected by the figure of a small sparrow presented in the foreground. He stretches his delicate body and, raising his head high, with his eyes points to an alternative vertical direction crossing the horizon line.

The skylark often appears in the works of Jacek Malczewski. In iconography, it is synonymous with the symbol of the sky, hope, spring, but also inspiration. “Merry skylarks become the clocks of the farmer”, as William Shakespeare describes these winged creatures in “Love’s Labour’s Lost”. They are the “pilgrims of the sky” who set the rhythm of the day, work and life. They are the link between the boundless, spreading sky above them to which they soar, and the earth on which they live, and from which they benefit. The trills and soaring of these birds symbolize the eternal desire to unite the earthly being with the heavenly, the human with the divine, the profane with the sacred. Recalling the words of the artist himself, expressing his desires and vision of the art he creates, becoming a kind of artistic manifesto, with the verses of his “His Song”: “And I shall fly like a skylark, and I shall fly up to the heavens”.