Description:

Jack Malczewski (1854-1929) inherited a love for art and romantic literature, especially the poetry of Juliusz Slowacki, from his family home. He came from a noble but impoverished family. His father Julian supported him on the path of a painting career. The events of 1863, the January Uprising and subsequent repression, left a deep imprint on the young artist. His first teacher was Adolf Dygasiński. The years 1867-1871 were spent at the manor of the Karczewskis in Wielgie. In 1873 he began studying at the School of Fine Arts in Krakow under the tutelage of Jan Matejko. He was a student of Władysław Łuszczkiewicz. He also studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He traveled to Italy, Vienna, Munich, Greece and Asia Minor. In 1896-1900 and 1910-1914 he was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. In 1912-1914 he became its rector. He began with idealizing realism, then naturalism, with the special theme of his works in this period being the exile of the Siberians and the inspiration of Juliusz Slowacki’s “Anhellim”. At the same time, fantastic and allegorical views began to appear in Malczewski’s work. After his father’s death in 1884, the recurring motif in Malczewski’s work was Thanatos – the god of death. After 1890 his art became thoroughly symbolic. Works manifesting the turn towards symbolism are “Introduction” 1890, “Melancholy” 1890-1894, “Vicious Circle” 1895-1897. The artist tackled existential, historical topics, concerning the position of the artist, his obligations to his homeland and the condition of art. He intertwined ancient and biblical motifs with native folklore and the Polish landscape so essential in his works. Form, color, monumentality of representations and their expressiveness became his trademark.

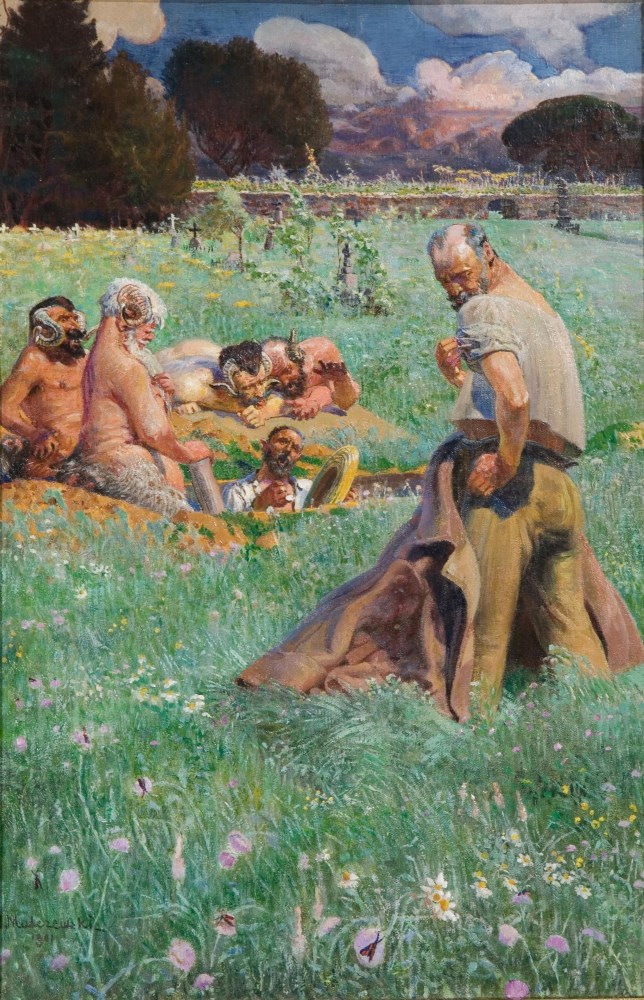

Description of the painting:

This time, Jacek Malczewski takes us to a sun-soaked, vibrant rural cemetery. In the foreground, among the blooming and buzzing meadow, we see the artist himself. His sagging Sybirak coat has revealed a white, shabby shirt, from which he takes off a field beetle. This occupation turns his eyes away from the freshly dug grave behind him. Inside, there is a bearded man. Taking off his straw hat, he directs his gaze at Malczewski, seeming to call him. Surrounding him are four figures, gathered around the bearded satyrs with goat horns. In the background, scattered among the meadow, are single graves, a group of bushes and a cemetery wall with an open gate. Behind it, a flowery field with single trees spreads out. Their conical crowns echo the milky-white clouds darkening in the depths of the sky.

It has long been noted that this small satirical-allegorical picture, kept in the style of Jan Stanisławski’s landscape, is an account of Malczewski’s artistic opponents, whom he depicted in the form of satyrs. On the left edge of the grave sits the corpulent Jan Stanisławski and Teodor Axentowicz, further down lies Konstanty Laszczka and Leon Wyczółkowski. This was a group of professors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, who, together with the rector Julian Fałat, visible in the grave, set the tone of the institution after the death of Jan Matejko. Malczewski did not agree with either the direction of the changes introduced by them, or the authoritarian-servile manner of managing this institution. He was also disgusted with the incessant intrigues and self-aggrandizement above other artists, which “he honestly could not stand”. This prompted him to leave the Academy. Just before that, in a letter to Karol Lanckoroński on 12 September 1900, he justified this, among other things, by introducing a new Statute of the University without consulting anyone, which would stop its development. “My withdrawal […] was intended – first of all to save the public good – a public institution – secondly, I wanted to clearly express my convictions, which are directly opposed to the convictions of the director of the institution in which I serve. ”** He therefore did not want to endorse his name with the new program, which not only deviated from the classical academic model of education, but also from the narrative in art, which was so important to him.

He also commented on his resignation in a satirical aquarelle from February 1901 entitled “Exit from the Academy”. We see almost the same group of satyrs with laurel wreaths on their heads (Laszczka was replaced by Mehoffer), who are sprinkling the fleeing satyr Jacek with easels and a plugged nose. The inscription over his head: “Deposit / humility towards nature / closed for an unlimited time” is an allusion to Stanisławski’s “absolute domination of the landscape – as an art devoid of narration and rejecting the composer’s creative imagination”. On the other hand, to Mehoffer’s brochure “Remarks on Art and its Relationship to Nature”, in which he pays homage to the modernism of Maurice Denis and the reflections of Paul Gauguin on the similarity of the harmony of the painting to the harmony of music. […] it also justifies the rule of the flat, framed spot of Art Nouveau transformed elements of nature, arbitrarily transformed by the artist. The creator can ‘destroy or magnify’ it, striving for stylistic unity of the painting”. For Malczewski, such a Secessionist deformation was as unacceptable as “the absolute submission declared by Stanisławski to the random capture – as he emphasized – ‘meaningless’ landscape.”

According to previous interpreters, the grave depicted in the Rogalinsk painting was supposed to be the burial place of the “Polish art represented by Malczewski, looking at the suffering soul of the nation, art ‘too little painting and too literary’, occupied by thoughts of the past and future. It is not without reason that Malczewski quotes on the back of the painting an excerpt from Słowacki’s “Grave of Agamemnon”. In this poem, the grave silence interrupted only by the sad ‘hissing’ of the grasshopper was an allusion to contemporary Poland.” *** A careful analysis of the mentioned painting and Słowacki’s poem, however, makes one wonder if the chosen fragment by Malczewski does not put the problem in reverse. Is there not here in fact a funeral of art represented by Fałat and his group of fauns? Is the painting not, like Słowacki’s poem, a reflection on the fate of the Academy and Malczewski’s call for them to abandon their weaknesses in order to rebuild their moral and artistic standards at the university?

Malczewski appears in the aforementioned watercolor, as do his colleagues in the form of satire. Here he is not. This may indicate that he does not identify with the purely Dionysian art of his colleagues by nature. He is also freed from the cricket, whose hissing emanating from the grave is “the terrible end of the rhapsody”. The cricket which wants to “command silence” to the artist. However, he continues to create, “opposing the crickets that welcome the warm summer with loud songs” (J. Kochanowski, “Muse” [vv. 10-12]). He remains faithful to his art, which is not limited to the sensual view of the world cultivated by his colleagues. As an adherent of the artistic views of symbolism, under the influence of Nietzsche, he believes that “the synthesis of the whole of life phenomena is possible only through the inclusion of the “elements of both gods – Apollo and Dionysus”. Therefore, the role of the artist is also to creatively comment on reality. For only the artist, like the Druid-poet from Słowacki’s poem, is able to “interpret from mythical transmissions of the past […] essential truths that would allow the humiliated Poles and Greeks to discover the “beautiful soul” in marble shapes, as is said of Leonidas.”***** And that this issue is paramount for Malczewski seems to be calling his colleagues, but also himself, to moral transformation, with Słowacki’s words:

Oh Poland! While you imprison an angelic soul

In a shabby helmet,

Until the hangman smashes your body,

Until your sword of revenge is not terrifying;

Until you have shame upon yourself—

And a grave—and eyes opened in the grave!

Throw off these abominable rags,

That fiery shirt of Dejanira,

And arise, like a shameless grand statue,

Naked—bathed in Styx mud!

New—boldly naked—

Unashamed of any kind—immortal!

Let a nation arise from the quiet grave

And the nations tremble,

That such a great statue—in one piece!

And so hard that it will not break in thunderbolts,

But with lightning has hands and a wreath—

A scornful look at death—the blush of life.

Poland! But you are deceived by sparkles!

You were a peacock and a parrot of nations,

And now you are a foreign servant—

Although I know that these words will not tremble for long

In the heart—where no thought lasts even an hour:

I say, I am sad—and myself full of guilt!