- Who we are

- History of the Museum

- Museum Stores

- Queries and lending

- Collections

- Ceramics

- Furniture

- Glass

- Metals

- Fabrics

- Miniatures

- Varia

- Our benefactors

- Exhibition

- Underground

- Ground floor

- First floor

- Second floor

Who we are

We are the only museum of applied art in Poland.

The museum collects objects of applied art from the Middle Ages to the present. These are skillfully crafted items, at the same time witnesses of changing tastes, fashions and styles. We tell a multifaceted story about the times in which they were made and the people they served through the exposed objects. They have been given a voice, because speaking about a man of past eras, his needs, interests, desires, says a lot about who we are today.

Sometimes going beyond the usual museum show, the exhibition works on different senses and encourages active exploration. The rich program of events carried out within many thematic cycles presents the museum collection more broadly, enriching the narrative of the permanent exhibition, but also going beyond it.

In 1857, the Poznań Society of Friends of Science (initially called the Poznań Friends of Science Society) was established, and within its framework the Museum of Polish and Slavic Antiquities was created in the Grand Duchy of Poznań; a significant part of the collections consisted of objects from the field of artistic crafts, often of a historical and patriotic nature.

1870 – From Seweryn Mielżyński for PTPN; among the paintings, drawings, coins and medals are crafts of practical art in it.

1882 – Opening of the Mielżyński Museum, built with a donation from Seweryn Mielżyński and public contributions; the exhibition included various objects of applied art, including historical memorabilia from different eras.

1885 – Establishment of the Historische Gesellschaft für die Provinz Posen (Historical Society of the Province of Poznań), which mainly collects artistic handicrafts from the Greater Poland region and local archaeological findings.

In 1893, the Provinzial Museum in Poznan was established with an Art and Crafts Department as part of its structure.

In 1902, the Provinzial Museum was renamed the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (Emperor Frederick III Museum); the museum’s structure included a Kunstgewerbeabteilung (Department of Applied Arts).

1903 – Transfer of 267 applied art objects from the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin to the Kunstgewerbeabteilung (Department of Applied Arts) of the KFM.

1904 – Opening of the new Kaiser Friedrich Museum building in Poznań

In 1906, the Ministry of Religions received the 222 objects from the Far East art collection of Professor Adolf Fischer, scientific attaché at the Imperial German Embassy in Beijing, purchased by the foundation of the secret commercial advisor, Dr. Hermann Paetel from Berlin.

In 1919, the Great Poland Museum was established, which took over the Kaiser Friedrich Museum collections and building; the establishment of the Art Industry Section in the Great Poland Museum.

In 1923, the Mielżyński Museum transferred its collections to the Wielkopolski Museum, including artistic crafts.

In 1939, the Great Poland Museum was renamed the Kaiser Friedrich-Museum Posen (KFMP), to which all the collections of the Mielżyński Museum and objects mainly from the Wielkopolska palaces, manors and churches seized by the occupiers were incorporated.

In 1945, the Wielkopolska Museum was restored and objects left by the Germans in various towns as well as the so-called “German property” from museum warehouses were added to its collections. A new department was established: Collection of Artistic Crafts – until 1965, artifacts of artistic crafts were displayed in various places of the museum and in the palace in Rogalin.

June 18th 1950 – Reorganization of the Great Poland Museum into the National Museum in Poznan (MNP), with a Department of Artistic Crafts including fabrics, metals, ceramics and furniture.

In 1950, Inventories of collections were established: Rz – Ceramics and Glass, Rd – Furniture, Rm – Metals, Mi – Miniatures, Rw – Fabrics, V – Variów.

1952-1953 – Incorporation into the MNP of a partially preserved collection of the Municipal Museum in Poznań

In 1965, the Museum of Artistic Crafts was established as a branch of the MNP, with its headquarters in the reconstructed part of Przemysł’s Hill Castle, the so-called Raczyński Building.

In 1991, the Museum of Artistic Crafts was renamed the Museum of Applied Arts.

From 2010 to 2015, the construction of the Przemysł Castle on Przemysł Hill and its connection to the so-called Raczyński Building took place.

In 2011, exhibition of the Museum of Applied Arts was closed.

2013-2015 – renovation of the Raczyński Building

2014-2016 – Organization of new warehouses and new exhibition of Applied Arts Museum in the combined buildings of Przemysł Castle and Raczyńskiego Building.

June 26, 2016 – Opening of the Industry Hall and Tower with Viewing Terraces

26 March 2017 – Opening of the new exhibition of the Museum of Applied Arts

Museum Stores

Between 2014 and 2016, modern and functional warehouses were set up for museums. Their equipment was adapted to the needs of different materials and guarantees the fulfilment of one of the main statutory tasks of the museum: to ensure the safety of the collections and to create the appropriate conditions for their storage. On the other hand, individually designed solutions enable full accessibility of the objects for documentation and research purposes in the place of storage.

Queries and lending

The National Museum in Poznan provides detailed information about its own collections.

Those interested in conducting a detailed inquiry or wishing to conduct it personally are requested to submit a written application to the Director of the Museum indicating the subject, purpose and scope of the research or to send it by email to: mnp@mnp.pl.

The museum does not provide information on the market value and authenticity of antique objects owned by private individuals.

Collections

The Museum of Applied Arts has around 12,000 items in its inventories, however some of them consist of multiple pieces. The permanent exhibition presents around 2,000 objects. Another approximate 2,700 museum objects are part of the permanent exhibitions of the National Museum in Poznań‘s branches: the Palaces in Rogalin and Śmiełów, the Castle in Gołuchów, the Museum of Poznań City History, and the Greater Poland Military Museum.

A large number of artifacts are loaned long–term to various museums in Poland, where they complement their permanent exhibitions for sometimes decades.

Often and sometimes in large quantities, objects from our collection participate in temporary exhibitions organized by Polish museums and cultural institutions, sometimes even abroad.

The ceramics collection covers all species of the field and counts about 3,500 exhibits.

The objects mainly come from European manufacturers, with fewer Far and Near Eastern products.The most impressive realization is a set of French floor tiles from the 13th century.In the small collection of stove tiles and floor tiles, the most notable object is a tile depicting Samson fighting a lion from the beginning of the 16th century, as well as a set of Dutch tiles from around 1700.

A varied and rich collection of faience includes both Italian maiolica, mainly Renaissance, and Central European faience created from the Baroque period to modern times. Dozens of products come from Delft, and other examples are from other leading centers, including Berlin, Hanau, Dresden, Rouen, Strasbourg, Nevers, Gien and Staffordshire. Polish faience is mainly represented by products from Pruszków, Nieborów, Paczków, Włocławek, Koło and Chodzież.

A large collection of Central European ceramics, ranging from Renaissance and Baroque pieces to 19th century works of historicism, is represented. English ceramics from Josiah Wedgwood and Böttger ware from Meissen are also included. Interesting Far Eastern pieces include vessels restored with the Kintsugi method.

Porcelain from the last three centuries, including Eastern and European varieties, as well as Polish production, forms a significant group in the collection. The Miśnieńska production is represented relatively frequently. Several pieces are from the famous Rococo Swan Service. European porcelain from around 1900 is another large group. Polish production is represented by porcelain from the 18th century to the 21st century, including those from Korcz and Baranówka, interwar works associated with the Poznań School of Artistic Crafts and Applied Arts, and modern dishes and figurines from the 1950s and 60s. A separate collection is the unique Polish contemporary ceramics, mostly created by artists from Gdańsk, Wrocław and Poznań.

The furniture collection consists of approximately 1400 objects and covers items created from the Middle Ages to the present. For the most part, they are European furnishings.

The collections stand out for their compact and interesting groups of Gdańsk (17th – early 20th century) and Silesian (18th – early 20th century) furniture. Gdańsk furniture comes partly from two historical collections, which gave rise to the collections: Poznań Society of Friends of Science and the German Emperor Frederick III Museum. Among them are cabinets characteristic of three different periods of Gdańsk carpentry: Baroque 2nd half of the 17th century and early 18th century, as well as Rococo 3rd quarter of the 18th century. Representative is the collection of Gdańsk and North European chairs from the 17th-19th centuries.

After World War II, which brought significant losses to the collections, a number of objects from the so-called Recovered Territories found their way into the collection. This is how the museum acquired a number of – also high-class – Silesian and European furniture, including a secretary with a depiction of the court of Solomon from the 20s-30s of the 18th century.

We have single pieces of furniture representing the most important centers and environments of modernity, including objects of Italian Renaissance furniture, single French and Italian furniture from the 18th century and from the Iberian Peninsula.

The collection of biedermeier furniture from the 1st half of the 19th century and from the period of historicism, i.e. from the 2nd half of the 19th century, developed interestingly after 1945. The set of equipment from the director’s office of the Emperor Frederick III Museum, designed in 1904 by the excellent Berlin architect Alfred Grenander, has been preserved. The collection of Poznań and Greater Poland furniture is also interesting. Among them are two objects from the late 18th century with a characteristic veneer of dark oak and single biedermeier objects. Of the local 20th century furniture, the most interesting are: a sideboard made around 1910 in the Otto Dümke company and a table in the style of Art Deco furniture from the well-known in the interwar period Józef Sroczyński Artistic Furniture Factory. An important set of “modern” objects created in the 2nd half of the 1950s and early 1960s in the circle of the then State Higher School of Fine Arts is also present.

The collection of over 900 pieces of glass includes mirrors, stained glass, hand-painted pictures on glass, and various vessels.

Objects from European factories from the Middle Ages to the present are represented. Examples from the 16th to the 20th century include painted glass with enamels, including stained glass and faience. Cabinet glass is presented with the technique of painting with transparent enamels.

High-class glassware is distinguished by both its artistic value and its origin. Examples include ruby glass, Venetian and Northern European vetro cristallo with its intricate shapes and decorations, dating from the 15th to the 19th centuries. There are also cut, engraved and wheel-engraved glass pieces with landscape and town views, battle scenes, hunting scenes, and portraits, coats of arms and mottoes.

Glass from central Europe, dating from the 17th and 18th centuries, is a prominent group. The most exceptional example of this group is a cup adorned with a raised relief by Friedrich Winter. High-quality heraldic glass is dominant among the products of Polish glassworks belonging to this group. A separate group consists of massive, polished, often colored Biedermeier glass, including so-called commemorative glass. The Historicism era is represented mainly by products from leading Silesian glassworks. Art Nouveau works, especially French and Austro-Hungarian, feature typical techniques, shapes and ornaments not seen before in European production. A small group of glass from the interwar period comes from Poland, Czech Republic, France and Germany.

In a separate collection of contemporary Polish art of unique character, alongside a large set of works by the Polish pioneer Henryk Albin Tomaszewski, the glass of the Wroclaw environment dominates.

The Goldsmithing, Jewelry and Non-Precious Metal Products Department gathers goldsmith, jewelry, chiseling (made of tin), watchmaker, turner (made of copper, brass, pewter or bronze), firearms (firearms) and armorers (armor and melee weapons) and blacksmiths, that is, everything made of metals and their alloys, also combined with colored stones, enamels, wood, ivory, shells or glass.

They present a very broad spectrum of antiques: from jewelry and personal trinkets, through furnishings and home decor – including clocks, to horse gear and weapons as well as vessels and temple equipment of various faiths: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant and Judaica, together with personal devotional items, made in Europe as well as in the Middle East and Far East, from the 12th century to the present.

The collection currently counts around 4,300 objects.

The exceptional object is a late Romanesque brass aquamanile in the shape of a lion made in Magdeburg in the 12th century.

Among goldsmithing works, significant groups create ceremonial Mannerist and Baroque Polish and German vessels from the 16th to 18th centuries and tableware from the 18th to 19th centuries, including those from Poznań.

Jewelry works are women’s and men’s jewelry – including costume accessories and personal watches, created in Europe from around 1500 to the 1970s. The most valuable jewel is a late Gothic gold merchant’s signet. Interesting are the gold Polish pocket watches with patriotic and religious decorations, made in Geneva in the third quarter of the 19th century in companies created by Polish watchmakers: Antoni Norbert Patk and Franciszek Czapka.

The collection of clocks includes both sundials and mechanical clocks from the late 16th century to the middle of the 20th century, mainly from Poland, Germany and England.

Significant is the arsenal of weapons: firearms, throwing, white, long and short firearms and protective armaments, made mainly in Europe and the Middle East, between the 4th quarter of the 16th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

The Department of Textiles Collection consists of decorative fabrics, apparel, fashion accessories, liturgical vestments, apparel and upholstery fabrics, and a collection of unique contemporary fabrics.

Some of the most valuable tapestries are from Western Europe from the 16th to 18th centuries, especially from the Flemish and Brussels manufacturies, including from the workshop of the Leyniers family.

The Eastern carpet collection, particularly Turkish and Persian, is adorned with two extremely valuable Polish tapestries. The collection of fabrics used for decoration is completed by Eastern and Polish makatas, made in various techniques and materials. Special recognition is due to the kilims from the interwar period made in Huculszczyzna, as well as in Gliniany, Okno and in the ŁAD Artists‘ Cooperative, with a large team of kilim projects from Wanda Grott‘s studio even before the First World War.

The collection of clothing gathered outfits from the late 18th century to the present day, including Polish noble outfits. It is complemented by collections of fashion accessories such as fans, shawls, umbrellas, headgear, handbags, wallets, and gloves. An important element of this set is the sash belts mainly from the 18th century, from many Polish, Persian, Turkish, Indian, French and Russian manufactories.

Among examples of various usable fabrics, the oldest objects come from distant South America from the pre–Columbian period.

The collection of vestments mainly presents copes and chasubles, created from the 15th to the 19th centuries and made of silk fabrics, decorated in various techniques, including embroidery. Among them, the most valuable are: a cope from the 15th/16th centuries adorned with Burgundian embroidery, and a cope with pretexte from the first quarter of the 16th century, according to tradition belonging to the Primate of Poland Jan Łaski.

A significant collection is a small, yet significant, collection of miniature portrait miniatures of Polish and European origin.

The core of the collection is made up of the collections of Edmund Rastawiecki (1805-1874) and the deposit of Antoni Madeyski (1862-1939).

The collection of the researcher and patron of art Edward Rastawiecki, mainly composed of Polish miniatures, was purchased in 1870 by the patron and collector Seweryn Mielżyński (1804-1872) and donated to the Society of Friends of Sciences in Poznań.

The collection stands out for its quality of works and stylistic and iconographic diversity. The best in the collection include works by Wincenty Lesseur, Anna Bacciarelli, and Anna Rajecka.

The collection of the collector and artist Antoni Madeyski was donated in parts in 1925, 1928 and 1929 to the Greater Poland Museum. The core of the collection is the European miniature with the largest group of the Italian school. Antoni Madeyski mostly collected miniatures of little known and unrecognized artists, among which there are also outstanding works, such as the portrait of a young man by Joseph Bordes or the ‘Female Portrait’ by Felicity Sartori-Hoffmann, a student of Rosalba Carriera.

The Varia collection consists of objects of an exceptionally diverse nature.

Varia usually make up the accessories for outfits and interiors, mainly women’s, men’s and children’s accessories. These are often small pieces of art made of ivory, jadeite, wood and amber. We have examples of glyptics among them, including Far Eastern ones.

The collection includes gems, canes, pipes, sewing tools, cufflinks, decorative figurines, glasses and their earlier counterparts.

It is also worth mentioning the collection of several dozen German secessionist book bindings and bookbinding projects from the 19th/20th centuries. A significant part of the Vari collection consists of various types of boxes, cases, and trinket boxes. These are mainly snuff boxes, boxes for cosmetics and accessories for clothing, or for writing utensils. Among them one can find examples of Far Eastern art, mainly from China and Japan, including expensive lacquer boxes.

Our benefactors

The collections of these institutions were largely developed through donations. Unfortunately, not all of the donated objects are currently in the museum, as its collections suffered considerable losses during the two world wars. Among the donors were representatives of the aristocracy and clergy, as well as prominent figures of the cultural and political-social life of Greater Poland, as well as ordinary citizens, and respected artists.

The list of benefactors of the museum throughout its history counts hundreds of names, as well as many names of cultural and social associations.

Exhibition

The permanent exhibition presents approximately 2000 museum items created from the Middle Ages to the present. European applied art predominates, among which are Polish works. Accomplishments of creators from other continents are shown from the perspective of the European. A narrative-based chronological arrangement was adopted, in which emphasis was placed on the meanings communicated by objects of applied art. The role of the object in the service of man was emphasized – in the material and spiritual aspect, in the private and public sphere. The chosen topics and arrangement in each of the rooms differently organize the space, referring to the proper ideological, aesthetic and artistic climate of the epoch.

The theme of collecting was highlighted, pointing to the historical conditions and the varied nature of collecting. Paths for children were set up, facilities for people with disabilities were provided and multimedia devices were introduced. The museum exhibition with its accompanying information and many elements enriching the knowledge of ancient objects, along with additional spaces for educational activities and broadly conceived meetings, creates a space for dialogue with both history and other people. In this broad discourse, the first place is taken by the virtuosically executed, exquisite work of art.

Exhibition Plan:

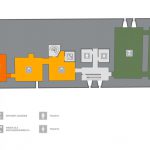

Underground

Treasury

In the castle’s cellars, museum treasures are displayed. The idea of a treasury as a special, difficult to access or even fortified room or building to store jewels, valuables, money and valuable state or family documents, namely the treasury, is materialized here. More than 130 of the most valuable, most impressive and most artistically or historically valuable valuables were presented: women’s and men’s jewelry – including clothing accessories, watches and objet d’art and gemstones.

Educational room

The space behind the Treasurer’s Office is designated for educational activities. The brick walls of the hall are the oldest preserved fragments of the original Przemysł Hill buildings.

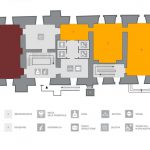

Ground floor

Przemysł Hall

A vaulted hall with two supports was designated to present the most important aspects related to the place (topographically) and the first owner of the castle erected here (historically). The exhibition focuses on four main topics: Industry II – Castle – White Eagle – History of Reconstruction.

Middle Ages

In the presentation of the art created since the 12th century, two threads were distinguished: the sacred (the sphere of holiness and spirituality) and the profane (the sphere of secular life) as inseparable aspects of the life of the contemporary man, permeating and affecting each other.

Armory

The exhibition referred to the Polish manor hallway, where weapons hung on the walls demonstrated the knightly history of the family and the bravery of the nobleman. Both European and Polish weapons, as well as Turkish and even Persian ones, were hung up. A division into Europe and the Middle East was adopted. In this arrangement, sets of melee weapons and long and short firearms were presented.

Renaissance

The Renaissance art exhibition was built based on four themes. In the central place a humanist table was created. This is a reference to the Renaissance secular and humanist trends, as well as the flourishing of sciences and the associated searches and discoveries. The table divides the room into two parts. In one of them, the art of Southern Europe, mainly Italy, where the direction referring to antiquity was formed from the beginning of the 15th century, was presented, and in the other, the products created at the same time in the areas north of the Alps. In the designated space, a Renaissance collector’s cabinet was created. This is a reference to the Renaissance Kunstkammer, which appeared in the 15th century and existed until the 18th century. The objects were exhibited in accordance with the Renaissance systematics. Naturalia were shown – extraordinary works of nature present in the surrounding reality of man, scientifica – scientific instruments and objects used to practice sciences, including sundials and mechanics, exotic – objects from exotic countries, showing the uniqueness and distinctiveness of the distant world, and artificialia – artistic objects created by human hand.

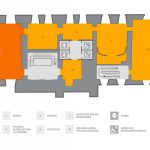

First floor

Baroque

To present the art of the 17th and early 18th centuries, two areas were chosen: Gdańsk and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Gdańsk was presented as the “Golden Gate of the Commonwealth”, through which culture and goods from all over the continent and overseas countries arrived to its vast areas, but also as a thriving cultural center. In the Commonwealth – the largest territorial state of Europe at the time, multinational and multi-confessional – a specific cultural and customs have developed. Sarmatism was highlighted – a special cultural phenomenon, associated with the noble class, characterized by pride, courage, love of Country, and a taste for the Orient.

Rococo

The exhibition displays the sophisticated elegance of the 18th century, known as the “century of porcelain”. In the middle of the room, a table evokes the courtly banquets of the time and presents the wealth of 18th century tableware. The sequence devoted to the rococo fashion shows the clothing and numerous products related to lifestyle. The arranged arrangement of shelves and consoles with porcelain refers to the collector’s interests and porcelain cabinets created at that time. Around the room, various objects were placed to complement the image of the era: furniture from various European centers, intricately decorated glass, mirror plates in carved frames, gilded geryons, ceramic oven, monumental tapestry and polychrome and gilded piano converted from harpsichord. In the center, a Venetian rezzonico glass chandelier is suspended.

Classicism, Empire, Biedermeier

The presentation of the art of the last decade of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century has been divided into three parts reflecting the different forms of fascination with classical patterns in the changing socio-political situation in Europe. A fragment of the interior – a cozy Biedermeier salon – has been created as a place of family life and social meetings, filled with a large number of characteristic equipment and small products made of various materials.

The exhibition refers to the nineteenth-century beginnings of modern European museology and evokes in two sequences the then museological activity of the Polish and German societies of Poznań.

Historicism

An impressive array of decorative works was presented in reference to the ideological and aesthetical diversity of the second half of the 19th century. During this period, admiring the old craftsmanship – the harmony between form, technology and usability – one took from the repertoire of ornaments of past eras, imitated old forms and rediscovered old techniques. The development of the presented art was connected to the needs of the new dominant social classes – plutocracy and bankers.

Meeting Room

A space devoted to activities of various kinds but with a common goal: discovery through meeting. Different forms have been introduced to enrich the discovery of the museum exhibit. While maintaining a few fixed elements, the arrangement of the room is variable.

The L. Wyczółkowski Collection

Presentation of the collection of the Polish painter Leon Wyczółkowski. Wyczółkowski’s collection is a testament to his passion that lasted 35 years. The collection was influenced by the artist’s tastes and enthusiasm. The items collected rather randomly had an important value – they created the atmosphere of the studio and served as painter’s props. Patterned fabrics, furniture, Far Eastern and Persian vessels can be seen on many of the artist’s watercolours, pastels and oils. Through the magnifying glasses placed next to the showcases, one can see the finesse of execution and the material richness of the presented items.

Second floor

Far East

The presentation of a Far Eastern art collection created by a Poznań museum at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, which mainly includes bronzes, ceramics, fabrics, and weapons components. In the second half of the 19th century, East collecting based on professional knowledge and expertise developed in Europe. The exhibition shows objects, some of which were produced as utilitarian items, but were imported to Europe as strictly collector’s items or for decorating interiors. It also showed so-called export production – specifically produced for the Western market and adapted to the tastes of Europeans.

Costume Parade

The exhibition presents costumes created from the 1880s to the 1960s. It showcases the transformation of fashionable silhouettes associated with the modeling of the female body and the degree to which it was exposed. It shows the process of changes that took place between the uncomfortable dress with the train, a manifestation of a woman’s constraint by conventions, and the freedom of a mini dress – a symbol of social revolution and a street fashion hit.

Secession

The exhibition was based on a set of objects created in many places in Europe at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. They come from different artistic centers, but express the same aspiration to shape the environment of man in a new spirit and to break away from the hierarchical division into pure and applied arts. The cult of the line emerged, which was used in aspects: structural, symbolic, ornamental and abstract. Organic strength of nature was exhibited. Following the discovery of Japanese art, a Far Eastern aesthetic appeared in European works. The exhibits illustrate the shift of the main emphasis from the cost of the material to the form and its elaboration using many new materials and techniques.

The 1920s, 1930s of the 20th century

The exhibition primarily showcases Polish art, which was free from involvement in independence ideas and embraced worldwide trends. The new political and social reality formed after World War I was full of significant cultural events. In the independent Poland, optimism accompanied the development of all areas of life. Examples of the popularized “national style” in Poland and Polish and European products in the elite art-deco style, developed in the 1920s, were shown. Examples of functionalism from the 1930s were also shown. The work of professors and students of the Poznan State School of Decorative Arts and Crafts, called “Zdobnicza”, draws attention to the significant development of Polish art education.

After 1945

After 1945, a clear divide between East and West Europe had a significant impact on the level of material culture on either side of the “Iron Curtain”. This exhibition presents outstanding examples of global design from different post-war periods and Polish design from the second half of the 1950s and first years of the following decade – the good times of Polish design. Products made of ceramics, furniture, fabrics refer to modernist artistic directions. The authors of the presented designs are mostly artists from the Institute of Industrial Design established in Warsaw in 1950. They were implemented in Polish factories that at that time were willing to cooperate with artists.

Contemporary Unique Art

The collection of contemporary Polish art, unique and gathered by the museum since the 1960s, documents the achievements of the first few postwar decades, when the main schools and trends were formed. The exhibition presents a wide range of artistic formulas related to three developing fields: fabrics, glass and ceramics.